By Anya Kohan

Photos by Marcus Branch

This past May marks 39 years since MOVE, a Black liberation group in West Philadelphia, was bombed by police. To commemorate this anniversary, an exhibit was created using artifacts, letters, and objects to examine the group’s history over time. Mike Africa Jr., one of the exhibit’s curators, is the son of two of the MOVE 9 members, Debbie Sims-Africa and Michael Davis Africa Sr. Born in prison after his parents were charged with the death of a police officer during a raid on MOVE’s headquarters in 1978, Mike dedicated his life to proving his parents’ innocence and carrying on MOVE’s legacy. MOVE: The Old Days, which was on view from May 12-19 at the Paul Robeson House & Museum, uplifts MOVE’s history through a selection of artifacts and archival materials. The West Philadelphia community continues to confront the reality of the state sanctioned violence that destroyed 61 homes in the neighborhood and killed 11 people, including 5 children.

In this interview, Mike Africa Jr. discusses how this exhibit came to be, what role archives and public exhibitions play in fighting injustice, and how he continues to push MOVE’s legacy forward.

KOHAN: For those who might not know, can you talk about the MOVE organization, its goals, and your relationship to it?

AFRICA JR: Alright, the MOVE organization was founded by John Africa in Philadelphia in the early 1970s. John Africa started the organization with a mission to protect life. Simple mission: protect life, people, animals, and the environment. And having that mission, MOVE would protest against the Philadelphia Zoo and the Bronx Zoo and other zoos around the country and also against the unjust treatment of animals. MOVE would protest at the Barnum and Bailey Ringling Brother Circus when they came to Philadelphia. Instead of signs that read “Barnum and Bailey’s Circus,” MOVE would write “Barnum and Bailey’s Sadism.” MOVE also protested against unjust prison sentences for black people and minorities, specifically the Black Panther Party. MOVE also protested against the issues of the environment, like at the water treatment plants where chemicals were being used to so-called “purify” the water, but was actually contaminating the water. So MOVE was just all around an organization that believed in protesting against any injustice dealt out to any forms of life– people, animals, or the environment.

KOHAN: Let’s talk about MOVE: The Old Days. What inspired creating this exhibit now?

AFRICA JR: What inspired creating the exhibit is a fallout between MOVE and other MOVE members with each other. There’s this infighting that has always been prevalent within the organization. And when people started coming home from prison, there was an influx of that infighting. And it was almost as if the members that came home from prison never resolved the issues they had with each other. They had these schoolyard, high school type personality issues with each other. This person liked this other person’s boyfriend or didn’t like something this other person said. They had jealousy issues. There were all of these crazy, immature issues they had with each other. And when they started coming home from prison, you would never know that those issues were there before, but when they came home, they came out. And myself, as one of the people who had been leading the movement to free the MOVE 9 from prison, I didn’t want any part of the infighting.

So as a way to kind of protect our legacy and protect my efforts to continue the work of MOVE, I took on this role of being the MOVE Archive Legacy Director. And at that point it was important for us to preserve the legacy and not have all the work we had done be diminished by people not getting along. So, you know, MOVE has a bad reputation for a lot of things over the years in Philadelphia. And over time, you know, my work and other people’s work had created an opportunity for some of that to subside. And I didn’t want my work to be in vain, so I wanted people to see MOVE for the positive aspects of it and not just these negative things.

KOHAN: You co-curated this exhibit with Professor Krystal Strong. Could you talk about the process of co-curating such a deeply personal exhibit with another person?

AFRICA JR: Well, Krystal is a very special person and her passion for justice and her movement in Philadelphia to talk about these issues of Black struggles has been the overwhelmingly powerful takeaway from her existence within this process. She is one of the founding members of the Philadelphia chapter of Black Lives Matter and just a very powerful presence. It wasn’t a hard decision to have her be a part of it. And now even to the point of being the MOVE Archive Director, she is very thoughtful about the way the items were selected and she’s very intentional about how those articles are explained. She wants people to understand the importance of MOVE’s history and the fight that MOVE had throughout its history. So, you know, I don’t even think it was a choice. It was just like the work that we had done together up to the point of the unveiling of the exhibit that was so natural and organic, it just happened. She exudes a very powerful presence and love for justice so she was just, you know, seamlessly involved.

KOHAN: In the film 40 Years a Prisoner, you said that you spent 25 years of your life searching for evidence that the MOVE 9 were innocent, for that “needle in a haystack” as you called it. How did you condense those 25 years into this exhibit?

AFRICA JR: I don’t think it was condensing 25 years, it was more like condensing 50 years. The exhibit didn’t just focus on the people that were in prison, it also talked about the early ideations of MOVE since before the people went to prison. This exhibit is an all-encompassing exhibit from 1972, even as early as 1970. It’s probably even earlier than that because John Africa’s idea is about freedom and what steps that need to be taken in order to see that through started before the above ground chapter of MOVE existed in 1972. And they continue on even after his tragic murder in 1985. So the way we chose what we chose, we just tried to be intentional about understanding what people needed to see to paint a full picture. It’s hard to choose items when you have so many, so we tried to just make sure that we captured the most vital points of the organization’s history.

KOHAN: I can imagine that would be an incredibly daunting task. And I understand that this exhibit utilized only 5% of the materials in the MOVE Activist Archive. Were there specific materials in the archive that didn’t quite make the cut for this exhibit that you wished had, and can you talk about them?

AFRICA JR: Yeah, there’s a lot of artifacts that we would love to have displayed, but some of them are really delicate because a lot of them were rescued from the fire after the bombing and it would have been nice to display some of those things. Also, we have some handcrafted furniture or handcrafted items that John Africa built himself that we would have loved to display, but just didn’t because some of those things are either hard to move around or it might take up too much of the exhibit in the space we had access to. When we get the full permanent location, we definitely would bring those things out. We have John Africa’s duffel bag that he had when he was in the military. We have some handwritten letters from my great aunt Louise, James Africa, who wrote to the military that they couldn’t locate John Africa when he was captured by Korean soldiers in the war. You know, there’s a lot of things like that that are personal items that show the family bond that existed before MOVE ever started, so hopefully we can display some more of those things later. But as of right now, we’re still working on getting that location.

KOHAN: Did you find anything in the archives that surprised you?

AFRICA JR: Yeah, you know, one of the things that surprised me a lot was how deep the infighting of MOVE actually ran. Going through some of these things, I’m finding letters where people were writing back and forth to each other from prison to prison, and even on the street to prison. And these feuds lasted for so long, it kind of gave me an eye opening understanding of some of this bitterness that people have within each other, blaming each other for the way things turned out, blaming each other for decisions people made that affected them. Some of the personal items where it gives you a better understanding as to how people just kind of threw away a really good opportunity of unity. I know they’re holding onto a lot of resentment for each other. And that was really surprising. The public display of MOVE has been a really strong sense of unity, but to see it played out through letters, there’s a deep level of infighting. It was very surprising.

KOHAN: Wow. And we definitely see that infighting within so many leftist social movements today–even though we all might have one goal we’re working towards, people get caught up in our differences. I’m wondering if you can speak a bit more broadly about the role of archives, preservation, and public exhibitions within social justice movements and what power you think they hold?

AFRICA JR: Yeah, there’s a saying that goes, “If you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat it.” And, you know, I think people need to understand what happened to MOVE so that they can know where to start from. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. If you do your research, you know that Africans were brought to America in chains by racist settlers that wanted to exploit our labor for their wealth. And if you understand the trauma that it generated, you know what to look out for. You understand what’s happening. You know, the IRA, Bobby Sands, if you understand that history and why they were fighting, then maybe that’s a way to understand the future and understand if you make this move, what you can expect the reaction to be. So museums and archives are really important because they tell a story as we don’t have to start from scratch when we’re talking about creating movements to fight oppression. And I think the MOVE archive is a really powerful archive because what happened May 13th, the bombing of MOVE, is not something that can never happen again. All of the things that MOVE was fighting against in 1972 were things that Dr. King was fighting against in 1968 that Malcom X was fighting in 1965 when he was assassinated and years before that, other people were fighting against these same issues. What led up to the bombing was just a group of people that was so tired of what happened to people and the injustice they experienced and they weren’t taking it anymore. They were willing to fight to the death. So those museums are important and I think that they should be supported so that people can understand our past so that we can make way for a better future.

KOHAN: On the tour, you said that your favorite part of the exhibit was that last room that viewers found themselves in. For people who didn’t get a chance to see the exhibit, can you talk about that room and why it’s your favorite?

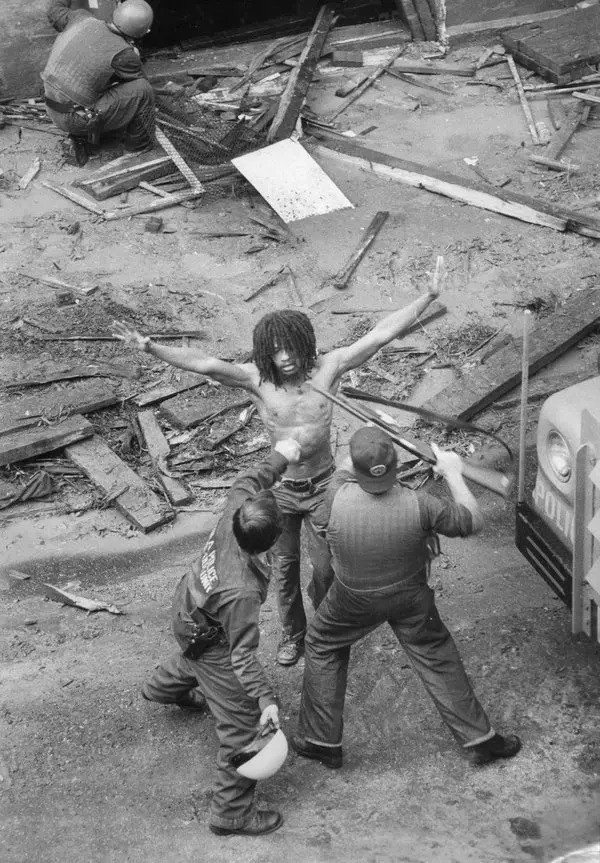

AFRICA JR: So we had a leg of the exhibit called “Free the MOVE 9”, where you saw people protesting and the flyers of the scheduled protests and events to talk about the MOVE 9’s imprisonment. And the last room was called Free the MOVE 9, where the work that MOVE people had done and supporters in the community, other activists, some politicians, some lawyers, it all led to the freedom of the MOVE 9. And in the middle is a picture of Delbert Africa with his arms outstretched, free. On August 8, when he was taken to prison, his arms were stretched out and he was preparing himself for the swing of a steel helmet that a cop swung and collided with his head and cracked his skull. And in that same photo, you can see the rifle that is in his face that was then turned and struck him in the jaw, breaking his jaw. And this is while he already had a shotgun bullet in his chest. And that August 8th arrest and beating of Delbert Africa was the image that a lot of people saw in the process of freeing the MOVE 9. But the “Free the MOVE 9” photo of Delbert with his arms stretched out was an image that was captured just minutes after he was released from prison after nearly 42 years. And that same pose, that same arm stretched out wide, was very powerful for me because on one hand you see his arms stretched out in the Jesus-like crucifixion of Delbert Africa. But then in the next photo you see an image of Delbert in the same pose, but it’s not crucifixion, it’s freedom. And so to see that, to see a picture of my parents hugging, getting a chance to get a free hug that they hadn’t experienced with each other for 40 years. There’s a picture of Janine that was right across from her husband, Phil. There was a picture of Murrow, who was right across from her husband, Delbert. To see those people come out of prison, despite all the infighting, despite the resentment they may harbor for each other, to see their release from prison after all those years of unjust imprisonment, it overrides any feelings of confusion or anger toward their behavior. It’s just a really good image to see after so many years of struggle.

Delbert Africa surrendering to Philadelphia police in August 1978

Photo by Philadelphia Inquirer

Delbert Africa after his release from prison in January 2020

Photo by Joe Piette

KOHAN: I understand that you’re hoping to make this a permanent exhibit at the house on Osage Avenue that was bombed in 1985, which this exhibit commemorated. Can you talk more about the Reclaim Osage movement and what reclaiming Osage looks like or means for you?

AFRICA JR: The Reclaim Osage campaign is about paying off the house that was bombed in 1985. So, after the bombing of MOVE and after the fire, the 10,000 rounds of ammunition and the 11 people that were murdered in that house, the city of Philadelphia took the house from my family through eminent domain. And since 1985, we’ve been trying to get it back. And my aunt Louise who owned the house, that was her dying wish. I had the opportunity to put a downpayment on the property through a lot of years of aggravation and fundraising. But, you know, that house is in the vicinity of the gentrification that is sweeping through Philadelphia.

So what my aunt paid for, I don’t know, $8,000 in 19-whatever, by the time it came around where I had the opportunity after the 30 years of eminent domain mark wore off, that house was no longer anywhere near what I could afford. $360,000 and then with the MOVE tax that the mortgage company put on it, it brought the price up to somewhere near $410,000. So I’ve been trying to raise those funds and use the logic of reparations to do it. We talk about reparations a lot, but what I’ve understood about black people and minorities getting anything, it always comes from a deep sense of love and fight. Reparations aren’t just handed to us. The slaves that got the chains off their wrists didn’t achieve that by the settlers or slave masters just having a change of heart and understanding that this is cruel and unusual punishment. That came from years of fighting and resisting and dying and killing and all sorts of behaviors that led to the freedom of Africans and black people. So the reparations that we seek today, we don’t expect Joe Biden or any other politician to just hand that over to us. It’s something that we have to work for and fight for. And that’s what Reclaim Osage is about. It’s about “do for the self.” It’s about working to take back what’s ours because it’s ours.

KOHAN: What do you hope visitors take away from MOVE: The Old Days?

AFRICA JR: I think the thing that I want people to know about is to learn the history so that people can understand that there are fights that you’re going to be involved in at some point. And, you know, you have to. It’s a really eye opening experience for the newcomer to revolutionary movements. You get a chance to see that if you take a stand against the system, this is what you have to face. If you take a certain stand and the certain decisions you make lead to certain things, although cherished and applauded and celebrated by a lot of people, it wasn’t an easy thing for MOVE members to go through. It wasn’t many MOVE members or ex-MOVE members or current MOVE members resent being a MOVE member because of all that they experienced. People lost their lives. People lost their children. People lost their families. They lost their homes. They spent years, decades, in prison without the connection to their husbands and wives and children and mothers and fathers, and it wasn’t an easy thing. And so this is what you have facing you. I think the reason people become revolutionaries is because they want to make a change. And what happened to MOVE isn’t something that can only happen to MOVE– certainly a lot of people believe that becoming a revolutionary increases your chances of being harmed by the state, which is a shame in itself. But the exhibit shows some of those lead ups and it shows some of those activities. It also shows some of the triumphs. You know, right now, today, there are people that enjoy not having to give blood when you are put in prison. Whereas when we went to prison, it wasn’t an option. You had to have a needle stabbed in your arm and a quarter of blood or however much extracted from your arm. If you were able to enter the general population, the stand that MOVE took made it where that’s no longer a law. So, you know, there’s a lot of positives to it, but there’s also some negatives. But the exhibit displays those things so that people can make that decision for themselves.

KOHAN: Absolutely. What other projects do you have coming up?

AFRICA JR: Right now, I’m doing what is called the 13 Run Challenge. The victims of the bombings, there were 13 of them. And 13 months from May 13, 2024 is the 40 year anniversary of the bombing. So every month for 13 months, I’m going to run 13 miles. I’m doing it around the country in different cities, and I’m doing it in honor of each one of the people that were bombed. Starting with the first one, which was for Ramona Africa. The last one will be for Bertie Africa, the child that survived the bombing. He was only 13 years old. And that run will be from the cemetery that he’s buried in to the cemetery that the other children are buried at.

KOHAN: That sounds like a really beautiful way to remember and memorialize them.

AFRICA JR: Well, one of the things I remember about them is the types of things we did together when we were children, which is run. As children, you naturally run and play together, we chase each other, you know? You fall and get back up, you keep on running. And so, you know, with MOVE being a very physically active organization that always believed in health and fitness, I thought that this would be the best way to honor them and the organization itself for the prosperity that I’ve been able to achieve through following in the footsteps of John Africa’s teachings.

KOHAN: How can people support you and MOVE?

AFRICA JR: They can support me by going to my website www.mikeafricajr.com and that does support MOVE because my work is directly tied to and connected to the work of MOVE. As the Legacy Director of the organization, I don’t think there’s a better person in a position to carry us forward anyway. So the activities that MOVE has always done, it’s the activities that I continue to do. So people can join up for the Run Squad and run with me on the next run. They can join the Cheer Squad if they can’t make it, they can support by donating to the GoFundMe we have, we’re trying to raise the funds to pay off this Reclaim Osage campaign which is, I think we owe $335,000. And you know, they can support that if people want to make a donation. If you’ve got a tax deductible donation, hit me up. Let’s talk about it. My email is mikeafricajr@gmail.com. I would love the support and hopefully we’ll see you at the permanent exhibit sometime soon when we get this mortgage paid off.

Join Mike on May 13, 2025 for the 13 Run Challenge that will be held here in Philadelphia. More details can be found on his website.