By the No Sister to Genocide Strategy Team

This article was initially written by the leadership of No Sister to Genocide as an internal report to serve our strategizing. It has been edited for the general public. We intend to continue to write regular reports and release them publicly when we can.

In 2025 amidst the ongoing genocide in Gaza, Philly Socialists resolved to sever the sister city link between Philadelphia and Tel Aviv, and contribute, in one small, material way, to unravelling the net of uncritical support the US gives to Israel. The two became sister cities in 1967, declaring they’re similar because both cities served as the places each nation declared its independence. In practice, as the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia describes, this is an ongoing agreement to continue “the exchange of delegations compromising political and business leaders, cultural representatives, educators, technical experts, and students.”

Ultimately, sister city designations lie under the jurisdiction of the mayor. But public pressure has ended them before, and the Boycott, Divest, Sanctions movement has highlighted sister city campaigns as a primary target in the movement to unravel the net of uncritical support Israel receives from the US. Our campaign, No Sister to Genocide, hoped to gather 5000 signatures from Philadelphia taxpayers vouching against the sister-city relationship. We were inspired by a similar campaign in Amsterdam in 2015 that won its demands after 4000 signatures. We know that Zionism is far more embedded in the US than it is in Europe and that Mayor Parker was unlikely to listen to us regardless of signature count, but we figured 5,000 signatures would at least demonstrate that we had the mandate of the masses and had “tried the easy way” so we could move to escalation. As institutional newcomers to BDS, we didn’t want to start swinging until we’d demonstrated our basic capacity to organize and the salience of our issue.

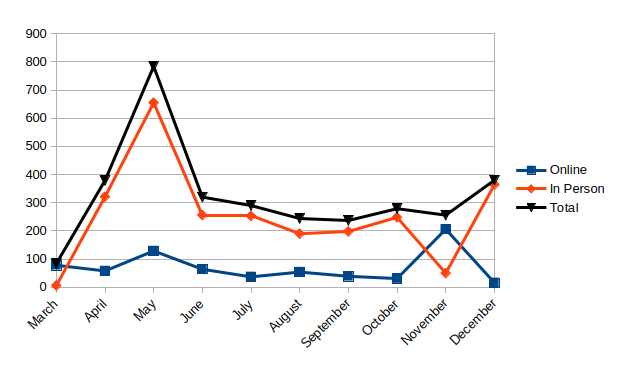

At the project’s initial proposal in February 2025, we predicted a launch within two weeks, a rally in March and 5000 signatures in April. These projections were delusional, a symptom of our organizers’ freshness, though of course they were only a guide. It took 9 months — late November — for our campaign to top 3000 signatures, and our pace of mass actions has been very slow. In this article we’d like to lay out some of our wins, challenges and lessons learned, to aid in collective decision-making, keep us accountable to the citywide Palestine movement, and teach others in the future who take up similar campaigns.

Ramping up

The campaign launched publicly in March. At first, we had few activities, focusing instead on research, strategizing, building unity, and configuring teams. There was one canvas on a quiet day in Malcolm X Park that was basically a dress rehearsal. The machine didn’t really get off the ground until April, but from there it was really running, and we canvassed every weekend if not more. We focused a lot on canvassing because if you’re focused on signatures, canvassing is just your best tool. People only scan flyers or sign stuff online if they are already especially passionate. If you walk up to them on the street, though, half of the time they will sign just because you’re nice. Of course, this also means that the pool of online signers is way easier to recruit from, which is definitely what the general interest meetings demonstrated.

During this first three-month period, we collected 1247 signatures off the strength of early buzz and weekly canvasses. In March and April, when we were developing our plan, we collected 84 and 379 respectively. In May, 784 signed. Most of our canvasses during this period were either at active rallies or in activist hubs like West Philly. For example, a single canvas targeting Clark Park earned us 161 signatures, while another at a craft fair in the Woodlands Cemetery collected 144 and a third at Porchfest netted 202. A general interest meeting we ran in Malcolm X Park in May pulled 25 people hoping to plug in, and another one we ran in June at the anarchist book store The Wooden Shoe pulled 20.

These areas self-select, however, and we did not want to trap ourselves in a red bubble. So, in June, we tried some exploratory canvasses like the Southeast Asian Market in FDR Park, South Philly along Passyunk Avenue by Marconi Plaza, North Philly near the Philly Mosque and Manayunk near the farmers’ market. Signature numbers dropped a lot. No canvas broke 100 signatures, and most came under 50.

Our reception did not change. People still liked us, mostly. Fewer signed, though, and we didn’t know the areas as well, so we had a hard time finding spots as densely packed as the Clark Park farmer’s market, and when we did, we often got quickly kicked out by event staff. We ended June with 320 signatures, and numbers slowed further in July and August. This prompted a real reckoning and a need to transform what our campaign was about.

Reckoning and refactoring

No Sister to Genocide found itself in a tricky bind. As a tool for social investigation, the canvasses were telling us we were ready for action. The issue was repeatedly shown to be hugely popular among all kinds of people. People are very politicized around this issue and are dying to do something about Palestine. Anecdotally, I’ve previously talked to strangers about building support for a strike, salting a building for a tenants’ union, gauging interest in a mutual aid distro, and repping Philly Socialists a few times. No Sister to Genocide is by far the most positively received cause I’ve ever canvassed for.

This did nothing towards developing the narrative that we’d “tried the easy way,” though. Even if we were hitting our metrics, it wouldn’t really mean we’d tried the easy way, as we were more and more acutely aware. To capture the attention of a politician, a petition must catch a large portion of the electorate — 50,000 signatures or, considering how entrenched Zionism is in this country, even more. Most municipal reform campaigns are started by NGOs with millions of dollars at hand, fleets of canvassers working 40-hour weeks and serious elite connections. We didn’t have those. We were burning out just doing what we were doing. In Marxist terms, the “objective” conditions in the world at large were present for us to make real change, but the “subjective” conditions in No Sister to Genocide were not.

At the July all-hands meeting, we put aside the usual agenda and invited members to share their feelings and frustrations. We decided to de-prioritize canvassing and focus more on coalition work (showing out to help with the other excellent BDS campaigns around the city), educational events, and light confrontations.

What’s next?

We believe that the correct strategy, and the one most respectful of everyone’s time, is to understand this campaign as one that will take years to level up to a win. We should, of course, be unafraid in the meantime to protest Zionists and stage confrontational actions. That said, there are a lot of other fights capturing people’s attention after a year of fascist escalation in the US, and we should be strategic with how our efforts build capacity in the movement at large. We don’t want to conceive of ourselves as isolated from or in competition with the other campaigns in the city, but as a new front capturing new terrain for the movement. Your average Philadelphian will never know the difference between No Sister to Genocide and “the Palestine people” overall. Our peers in the struggle will appreciate us more for being conversant with their efforts.

But even as we collaborate with our comrades, we will not stop with our organizing. Nor should we ignore the success we had in growing the campaign. When No Sister to Genocide began, 26 people joined. Today, we have 90 members, mostly real contributors. Some of these folks were already active in other campaigns, but most had never really gotten involved in radical organizing before No Sis appeared. This means we have been pretty damn successful at building militants, which is always a prime goal of these sorts of campaigns.

Looking ahead, conceiving ourselves as a long-term campaign means putting more focus into our flyering and communications teams, who have already been putting great work. At our general interest meetings we always poll people on where they heard of us. A near majority tells us they’ve seen us on a flyer, a slightly smaller portion hears about us from a friend or a speech at a rally or the like, and only one or two have ever been approached by a canvasser. We should still canvass when we can, ideally once a month still.

If we want to stay viable, however, we will need an anchor point, something to do even if there is no motion for months on end. Iglesias Gardens, for example, is always launching new land fights with the city, but even when they aren’t, they have a cool garden and community center so people stay steeped in the work. CARP can fight City Council about mobile distro bannings and then return to its own weekly distro and help Philadelphians in need. Without some kind of anchor point, though, every month that passes without a win will feel more like a clear loss.

Our best suggestion for this, which first came from a comrade in the campaign, is to start developing our own sister city relationship with a new Palestinian city. If we research properly and connect with people in Ramallah or Gaza who are also excited about staying in touch with us, we could set a regular cadence of teach-ins, video calls, and politicized fundraisers. This would make an immediate difference in people’s lives, produce small wins, build unity and trust, and teach us a lot, without a lot of risk. Doing this would also transform our campaign into one that is building towards a new more beautiful relationship and not based purely on ending an odious one.

Postscript: There hasn’t even really been a dip in signature rates since we retooled the campaign around building capacity and coalition work; we still bag around 250 a month, and in December we canvassed 6 times. Having more hands also means that canvasses are much easier to bottom-line than they were in the summer.